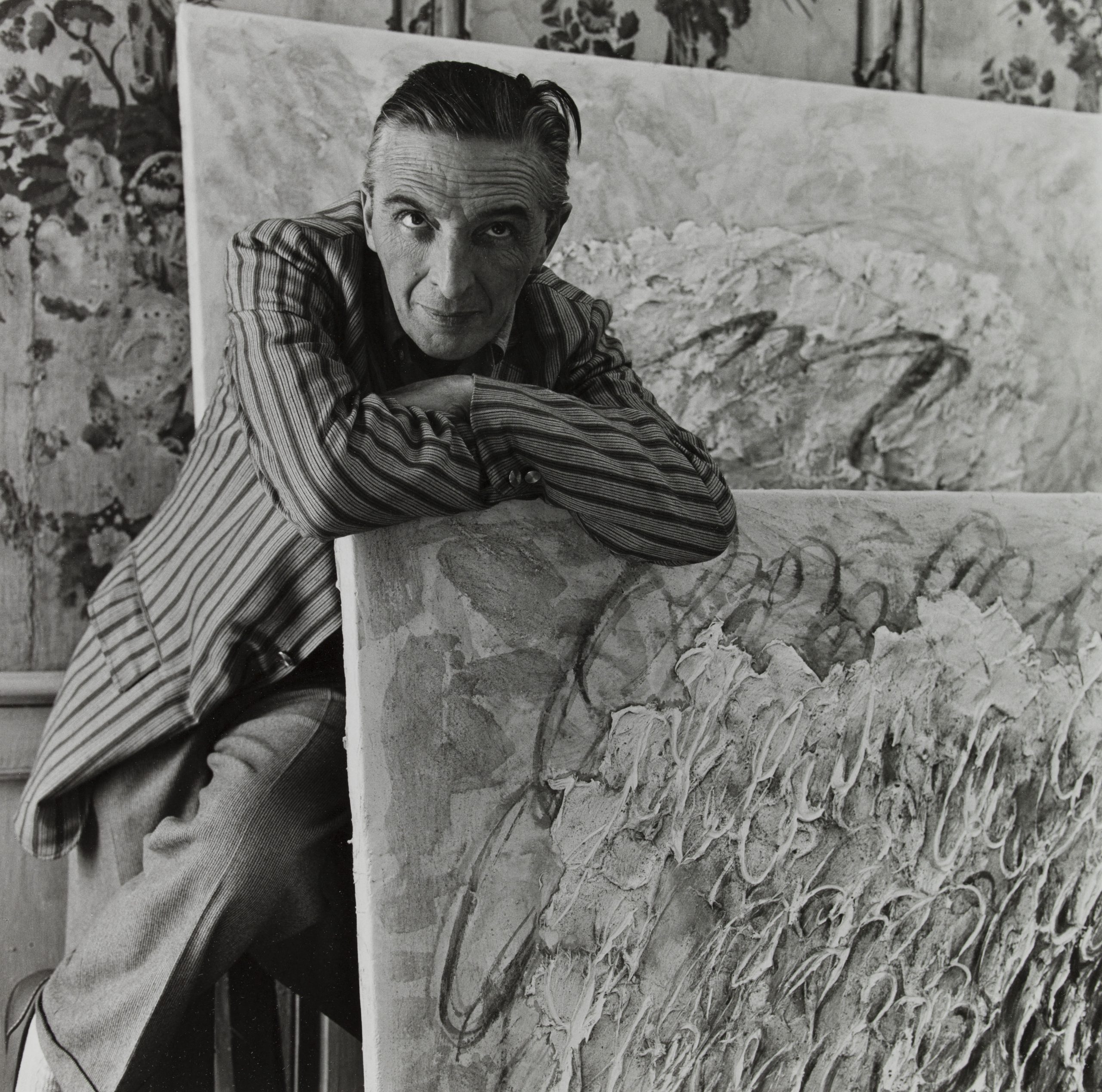

Jean Fautrier

1898 - 1964

Although it is true that Fautrier’s work presents two “possible attitudes to reality,” as he himself says, he continues: “Even though they are apparently incompatible, they in the end converge and attain the same end by opposite approaches… The unreality of an absolute ‘informel’ contributes nothing. Pointless. No form of art can provide emotion if it does not include at least some reality. However minute this may be, however intangible, this allusion, this irreducible fragment is the key to the work. It makes it understandable; it clarifies the meaning, it opens up its profound basic reality to the sensitivity of intelligence. We only reinvent what is, recreating in shades of emotion the reality incorporated in matter, form, colour, products of the instant, changed into what can no longer be changed.” This statement sufficiently underlines the ambiguity of the artist, who despised his early works. The painter of multiple experiences, he paradoxically became the precursor, with Wols and Dubuffet, of the movement which was later called ‘Art Informel’, breaking with figurative expression during the Second World War. In a text written in December 1958, Fautrier explained his commitment: “As man gradually becomes more civilised and refined, he frets and his mind wanders in search of transient sensations which he barely grasps – he is no longer satisfied with straightforward emotions. It is perhaps within this condition of the modern mind that we should find the explanation of this informal rage… In art, only the quality of the artist’s sensitivity counts, and art is only the means of externalization, albeit a mad means, without rules or calculation. Painting is something that can only destroy itself, which must destroy itself in order to be reinvented” (Parallèles sur l’informel, published in Blätter + Bilder no. 1, Wurzbourg. Vienna, March–April 1959).

“ The subject becomes a pretext for a thick powerful style, purely pictorial, which explains the earlier paintings. We find a very rich temperament here, with tragic resonance… intense color, accomplishing the essential through sacrifice (the embellishments and scrapings of 1927 have disappeared) … Each of these paintings seems violently spontaneous… showing a desire to preserve only the strongest or most acute sensations. ”

Let us consider the different phases of this first period, which was to be so important for those that were to follow. After the death of his father, when he was 10 years old, he went to live with his mother in London and took her name. At 16, he entered the Royal Academy School where he was taught by Sickert, before moving to the Slade School, more open to modernism. Disappointed, he worked alone and visited the Tate Gallery. From this training, he acquired a faultless technique already considered by his English teachers as too brilliant, and which was nevertheless unanimously recognised by both his admirers and detractors. This technical brilliance was to play an essential role in Fautrier’s itinerary. Called up in 1917, he returned to France and was discharged in 1921.

Fautrier painted in a style of marked realism, showing at the Salon d’Automne for the first time in 1922 with Tyroliennes en habit du dimanche (Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris).

In 1923 his first fundamental meeting occurred with Jeanne Castel at the Galerie Fabre in rue de Miromesnil, where Fautrier was showing his work. Her husband, Marcel Castel, had a garage in rue du Général Beuret, and the couple were keen art lovers. A few months later Fautrier showed 10 paintings at the gallery, and Jeanne Castel became his first collector.

In 1924 he had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Visconti, which was noticed by the critics, followed by a second exhibition at the Galerie Fabre. Jeanne Castel introduced him to Paul Guillaume, who for seven years provided him with financial support. The dealer Zborowsky also showed interest in Fautrier’s paintings, which he exhibited with the works of Modigliani, Kisling and Soutine (1926). The latter’s subjects were moreover close to those being painted by Fautrier at the time: skinned game, rabbit skins and wild boars, whose hanging, sacrificed flesh reflected an interiorised suffering and horror which he attempted to exorcise through a style of sombre expressionism dominated by browns and midnight blues. This work brought him fame and he moved into Gromaire’s former studio in rue Delambre, which he occupied until 1934.

Oil on canvas

162 x 130 cm

Mixed media on paper laid down on canvas

81 x 100 cm

In 1928 André Malraux, whom Fautrier had met at Jeanne Castel’s, suggested that he illustrate a text of his choice. He decided on Dante’s Inferno. After signing the contract with Gallimard in 1930, the plates were subsequently considered unpublishable because of their disconcerting novelty, and by 1945 the project had been abandoned. A series of lithographs were made, however, and shown in 1933 at the gallery of the Nouvelle Revue Française (NRF). In 1928 Fautrier had his third solo exhibition, organised by Paul Guillaume at the Galerie Bernheim at Jeanne Castel’s request. Malraux published an important text in the February issue of the NRF: “The subject becomes a pretext for a thick powerful style, purely pictorial, which explains the earlier paintings. We find a very rich temperament here, with tragic resonance… intense colour, accomplishing the essential through sacrifice (the embellishments and scrapings of 1927 have disappeared)… Each of these paintings seems violently spontaneous… showing a desire to preserve only the strongest or most acute sensations.” To follow this evolution, let us briefly mention these successive phases of realism, which came to a head in 1925. Studies of nudes in charcoal and then in pastel prefigure the ‘période noire’ (black period), at the same time as a series of mountain landscapes made around 1926 to 1927. In the series Glaciers, he pays tribute to Turner, whom he had so admired in London. He manages to suggest blocks of ice by using white impasto, a treatment of texture which prefigures the sobriety and understated expression of his spangled material characterised later by Otages. The période noire, a term employed by Fautrier himself, begins with Sanglier écorché (Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris), exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in 1927, and covers an entire year. From 1928 we can see a lightening of his palette, with an increasing preference for ochres and greys, the paint becoming thinner and the still lives losing their tragic dimension. The subject gives way to space. The artist had already experimented with techniques that he perfected during this first period. His new pictorial process finally emerged around 1940. Since 1929 he had preferred paper to canvas, which would then be laid down. He worked using flat tints after first preparing his paper with a whiting coating and glue, a strong preparation that was nevertheless transparent. He then drew his subject in inks using a brush. Powders or fluid materials such as watercolour or gouaches were spread onto the wet coating, on which he laid a first coat of paste following the outline of the drawing. Further coloured powders were spread, after which the artist superimposed additional unequal coats of paste with the use of a spatula. Coloured powders were then again spread, some settling on the still-fresh paste. He then applied light glazes in subtle shades over these coats. The drawing tackled again with a brush on the paste that had covered the initial drawing and around it where it had remained visible. He then used a cutter to draw furrows in the paste and complete the image.

The economic crisis of 1929 to 1930 struck the art market and affected young artists such as Fautrier.

In 1931 he showed for the last time at the Salon des Tuileries and the Salon d’Automne. In 1934, penniless, he stopped painting and left for Tignes, where he became a skiing instructor and opened a nightclub, La Grande Ourse, at Val-d’Isère. In 1939 he visited Marseille, Aix-en-Provence and Bordeaux. On his return to Paris in 1940 he stayed with Jeanne Castel in rue du Cirque and resumed painting. The following year he found a studio at number 216 boulevard Raspail and met Paulhan, Char, Ganzo, Ponge and also Eluard, whose works he was to illustrate.

In 1942 he showed at the Galerie Poyet, and Madame Edwarda by Georges Bataille and Orénoque and Lespugue by Robert Ganzo were published by Georges Blaizot. Arrested in January 1943 and then released, he left for Chamonix. On his return to the capital, he settled at Châtenay-Malabry, where he was to live and work for the rest of his life. Around this period he finally broke with figurative expression.

In 1943 the Galerie René Drouin showed his works made between 1915 and 1943 with a text by Jean Paulhan and, in 1945 also showed the series Otages, consisting of paintings and sculptures, accompanied by a preface by André Malraux. The public had difficulty in perceiving what the artist had wanted to express, and reactions were often sharp: backgrounds appeared to have been mistreated by a trowel, an obvious provocation, although this contrasted with a degree of delicacy in the manner of drawing and an attractive palette. An entire new generation would be inspired by his work. A violent indictment of crime and massacres, his works show us the emergence of reality, beyond simple appearances. There is no distancing between the visible and the work, nevertheless what we might refer to as the logic of the relationship between lived and evoked is destroyed. The texture recreates reality through substance rather than representation. The early hostages are still identifiable though: “Little by little Fautrier does away with direct suggestion of the blood, and the complicity of the corpse. Colours [allusion to greens and pinks, which are almost tender] free of any rational connection with torture replace the earlier tones; at the same time as a line that attempts to express the drama without representing it replaces the haggard profiles… hieroglyphics of pain,” wrote André Malraux. The following year, Francis Ponge wrote his Note sur les Otages, peintures de Fautrier. The poet commented on the constant presence of a form of logo, a sort of T placed within an O. Michel Ragon mentions a cross, “the crucifixion of twentieth century man.” After Otages, Fautrier painted in 1956 Têtes de partisans. In 1947 Blaizot published Alleluiah by Georges Bataille, and La femme de ma vie written by André Frénaud and illustrated by Fautrier. The artist then worked on the illustrations for a book which Jean Paulhan had written about him, Fautrier l’Enragé, which was published by Blaizot in 1949 with an exhibition with the same title held at the Galerie Billiet-Caputo.

In 1950 Fautrier and Jeanine Aeply (with whom he had lived since 1943 and by whom he had two children) developed a process of reproduction ‘en épaisseur’ (‘in thickness’), and Fautrier experimented with Originaux multiples, shown the same year at the Galerie Billiet-Caputo with a text by Jean Paulhan titled Les débuts d’un art universel. Making multiples would enable a wider public to have access to works of art. This exhibition had been preceded a few months earlier by one titled Aeply Replicas at Gimpel Fils in London.

Fautrier repeated the experience in 1953 at the gallery of the NRF, and in New York in 1956, but it was not however a success.

In 1954 he began work on a new series, Objets, boxes in cardboard or in iron-white-cage-bottle-key-glass-coffee mill, which had been prefigured by certain works of 1947. Les objets de Fautrier were shown in 1955 at the Galerie Rive Droite with a catalogue text by Jean Paulhan, titled Un jeune ancêtre, Fautrier. Not a single work sold. André Berne-Jouffroy wrote an important study in the May issue of NRF, in which he says: “Fautrier paints a box as if the concept of box did not yet exist; and, rather than an object, a debate between dream and matter, tentative steps towards ‘the box’ in a realm of uncertainty where the possible and the real combine… Fautrier offers us objects in their nascent condition, offering them to us through something resembling painting but also reinvented, rediscovered in its nascent condition… Dreamed only.”

The paintings were shown again at the Alexandre Iolas Gallery in New York in 1956 with a text by André Malraux titled Lettre à un jeune Américain.

Then came the series Nus. An exhibition of 17 nudes, painted between 1945 and 1955, was given at the Galerie Rive Droite, with a catalogue text by Francis Ponge, who saw in them a conjunction of bodies and flowers. “Flesh combined with dresses, as if steeped in satin, here is the substance of flowers.”

The invasion of Hungary by the Soviet army inspired Fautrier to make a series shown in 1957 at the Galerie Rive Droite under the title Les partisans, a tribute to the rebels of Budapest. Since 1955 he had once more taken up the subject of the components of landscape, on which he had already worked in 1943: Les fougères, Forêt, Branchages, Herbes and Fruits.

Let us return to Fautrier’s highly personal technique of working in successive phases, a technique analysed by Palma Bucarelli in Peinture et Matière (Il Saggiatore, Milan, 1960). From the 1950s onwards, the impasto is created using a coating similar to the plaster used for stucco, but which hardens faster, although the surface remains malleable for a while. The artist projects on to this substance pastels or undiluted coating powder. The initial drawing is constantly re-commenced, sometimes using a brush with touches of oil paint. From 1956 to 1957, Fautrier worked on the ‘buvards’, oil paintings done on blotting paper. Extremely precise and attentive to anything concerning ‘texture’, which he regarded as an integral part of creation, Fautrier was virtually an alchemist, making his colours himself.

The ‘informal’ concept was established as a theory and school by Michel Tapié in his book Un art autre, which appeared in 1952 in conjunction with an exhibition under the same title at the Studio Facchetti, and which included Fautrier under its abstract section. In 1951 Michel Tapié had already shown Dubuffet, Michaux, Mathieu, Riopelle and Serpan in the exhibition Signifiants de l’Informel at the same gallery. A number of monographs appeared on Fautrier and contributed to making his work known. Fautrier by Michel Ragon, collection du Musée de Poche, Fall, 1957; Fautrier 43 by Robert Droguet, Besacier, Lyons. Fautrier by André Verdet, Falaise, Paris, 1958. Fautrier d’un seul bloc fougueusement équarri, in Mercure de France, 1959. Fautrier et le style informel, by Pierre Restany, Hazan, October 1963. There was also a film directed by Philippe Baraduc, Fautrier l’Enragé, a dialogue between Jean Paulhan and the artist.

During these years there were a number of major, and often retrospective, exhibitions. Trente années de figuration informelle, Galerie Rive Droite, 1957; Galerie André Schoeller, works on paper, with a catalogue text by Restany and historical notes by René Drouin. 1958, Gouaches et dessins informels de Fautrier de 1928 à 1958, Galerie René Drouin. This was to be his last exhibition in Paris.

There were an increasing number of exhibitions abroad: New York in 1957, Dusseldorf, Barcelona, Madrid, Turin, Milan, Rome, Bologna, London, Lausanne and Stockholm.

In 1958 Fautrier visited Japan accompanied by Paulhan, and the following year his work was show in Tokyo at the Minami Gallery.

In 1960 Fautrier was the Guest of Honour at the Venice Biennial, receiving the Grand International Prize in Painting and in 1961 the Grand International Prize at the 7th Tokyo Biennial.

A solitary and exacting man, Fautrier did not open up easily and did not participate in any of the salons. He did, however, participate posthumously in the 1964 Salon de Mai with a sculpture, Brisures, released by Michel Couturier with whom, in 1958, he had signed an exclusive world contract for all the works executed after 1950. Around 1960 he reprinted a number of old plates and published some new prints with the printer Jacques David. Sculpture, which had been a part of his work since the early years, followed the same course as his painting. In 1964 Fautrier made an important donation to the Musée de Sceaux (which notably included the series Otages), as well as a donation to the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, which held the first official retrospective. Seriously ill, he worked on the exhibition from his bed but died on 21 July, before the exhibition opened. A number of exhibitions followed, of which a complete list is to be found in the catalogue of the 1989 Fautrier retrospective held at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

1986 Fautrier 1940–1964. Galerie di Meo, Paris. Catalogue, text by Castor Seibel.

1990 Fautrier. Galerie di Meo, Paris. Catalogue, text by Christian Derouet.

2014 Jean Fautrier. Tokyo, Station Gallery; Toyota, Municipal Museum of Art; Osaka, The National Museum of Art. Catalogue.

2017 Jean Fautrier. Kunstmuseum Winterthur. Catalogue.

2018 Jean Fautrier, Matière et lumière. Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris. Catalogue.

It is impossible to mention here the many museums throughout the world which conserve works by the artist.

- Pierre Cabanne: Jean Fautrier, Classiques du XXIe siècle. La Différence, Paris, 1988. Biography. Complete bibliography.

- Yves Peyré: Fautrier. Regard, Paris, 1990.

- Rainer Michaël Mason: Nouvel essai de catalogue raisonné, œuvre gravé. Cabinet des Estampes, Geneva, Galerie Tendances, Paris, 1986.

- In preparation: Marie-José Lefort: Catalogue raisonné of Fautrier’s work.

Excerpt from L’École de Paris 1945–1965: Dictionnaire des peintres

Ides et Calendes Editions, courtesy of Lydia Harambourg

www.idesetcalendes.com

les artistes

- Karel Appel

- Jean-Michel Atlan

- Martin Barré

- Jean-René Bazaine

- Roger Bissière

- Victor Brauner

- Camille Bryen

- Serge Charchoune

- Corneille

- Olivier Debré

- Jean Dubuffet

- Maurice Estève

- Jean Fautrier

- Otto Freundlich

- Roger-Edgar GILLET

- Hans Hartung

- Jean Hélion

- Auguste Herbin

- Asger Jorn

- Wifredo Lam

- André Lanskoy

- Alberto Magnelli

- Alfred Manessier

- André Masson

- Georges Mathieu

- Serge Poliakoff

- Jean-Paul Riopelle

- Gérard Schneider

- Pierre Soulages

- Nicolas de Staël

- Victor Vasarely

- Bram van Velde

- Geer van Velde

- Maria Elena Vieira da Silva

- Otto Wols

- Zao Wou-ki