Victor Vasarely

1906 - 1997

The immediate heir to the ideas of the Bauhaus, Vasarely may be considered as one of the major representatives of kinetic art. Early on he reached two certainties from the teaching of his master Alexandre Bortnyik: first, that abstract art should perform a role in changing the urban environment, and secondly, that he should break with easel painting to accomplish total plastic creation.

In 1927 Vasarely stopped his medical studies at Budapest University to attend classes at the Podolini-Volkmann Academy. From 1928 to 1929 he was a pupil at the Muhely Academy (referred to as the Hungarian Bauhaus), run by Alexandre Bortnyik, who had returned from the Bauhaus in Dessau and Berlin (where the demise of art was often discussed), still influenced by the teaching of Albers, Moholy-Nagy and his contacts with Klee and Kandinsky. The young Vasarely was profoundly influenced by the lectures Gropius gave in Budapest, in which the latter stigmatised the image of the ‘artist tramp’, advocating inspiration related to talent and an entirely new functionalist identity based on scientific foundations. These two years of study were decisive for Vasarely who acquired sound skills in drawing that enabled him, as he said himself, to execute “trompe-l’oeil just as well as new ways of drawing.”

“ Abstraction was only really revealed to me in 1947, when I was suddenly able to recognise that pure form and pure colour signify the world. ”

After a successful period as a graphic designer in the advertising business in Budapest, Vasarely emigrated to Paris, where for the next 15 years he designed posters, models and illustrations for leading companies and agencies such as Draeger, Havas and Devambez. He took French nationality. From 1935 he created a number of series on themes such as Echiquiers, Tigres, Zèbres, Arlequins and Martiens, which were the beginnings of his kinetic art, employing axonometric deformations. His early work is difficult to distinguish from his work for advertising, with drawings in black and white, marked by a particular interest in movement, which was to become central to his work.

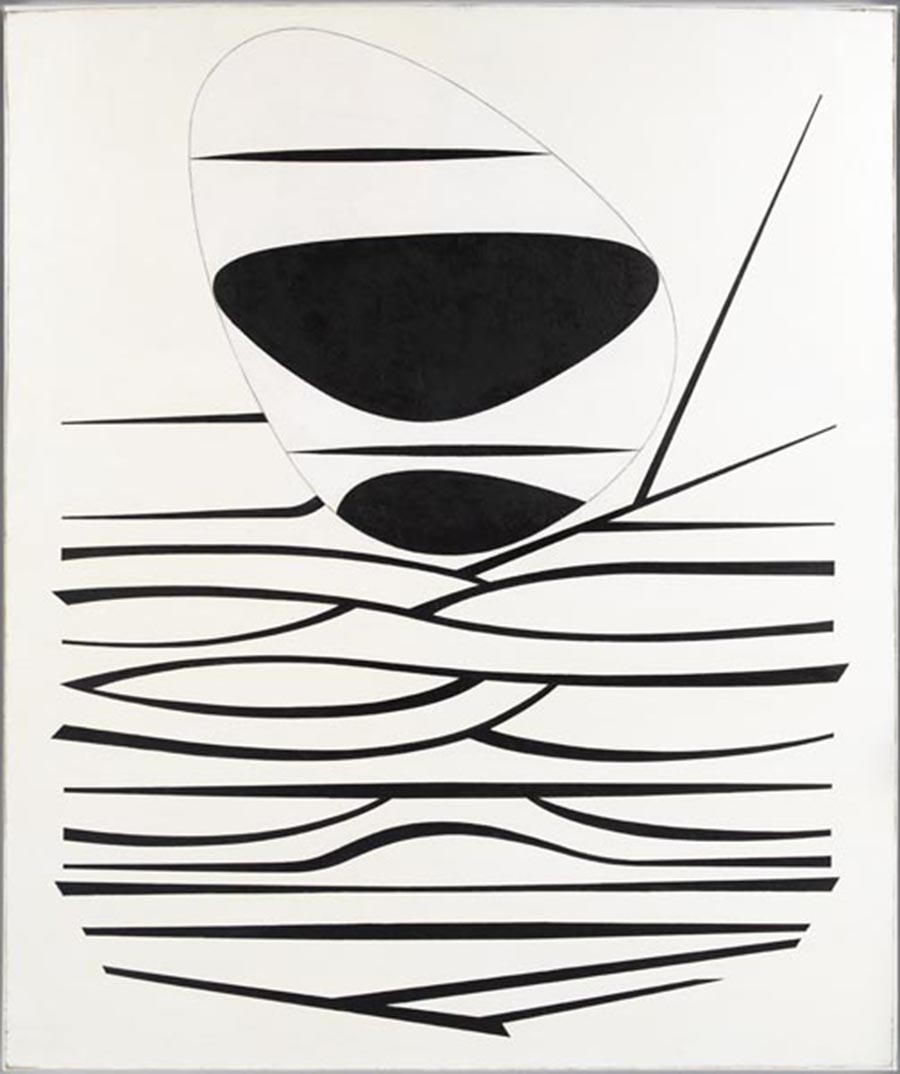

Playing with optical phenomena, the model is suggested by the deformation in certain precise places of regular oblique lines that cover the painting’s entire two-dimensional space. We see this in Zèbre, where the forms are evoked by deforming the twisting lines that provide volume, prefiguring the later undulating works, and in l’Arlequin and l’Echiquier, with their arrangement of black-and-white squares, in which the series Algorithmes of the 1960s and Martiens had their roots, where the bodies are formed by the enlargement of squares, leading to Gonflages, and finally Têtes, placed on the six faces of a cube, with an axonometric perspective based on the superposing of an identical element (a square, or sometimes a hexagon), creating an illusion of volume and space that has not been deformed. Vasarely considered this research as “the basic repertory of the abstract kinetic period, begun in 1951 and fully developed from 1955”.

During the Occupation, Vasarely returned to painting still lives, landscapes and portraits. In his quest for his true path through his various experiences, questionings and ‘wrong directions’, he moved towards reducing the object to a diagram. He spent 1944 on his painting. He was the co-founder of the Galerie Denise René, which opened in November of that year at number 124 rue de la Boétie, with his first solo exhibition. He had regular exhibitions at the gallery from then on. He rapidly became the driving force of the form of abstraction referred to as ‘constructive’. He had a second exhibition in June 1946 with a text by Jacques Prévert. Among the still-figurative paintings, marked by a simplified symbolism, was Le metre and Sept ans de malheur.

Oil on canvas

120 x 100 cm

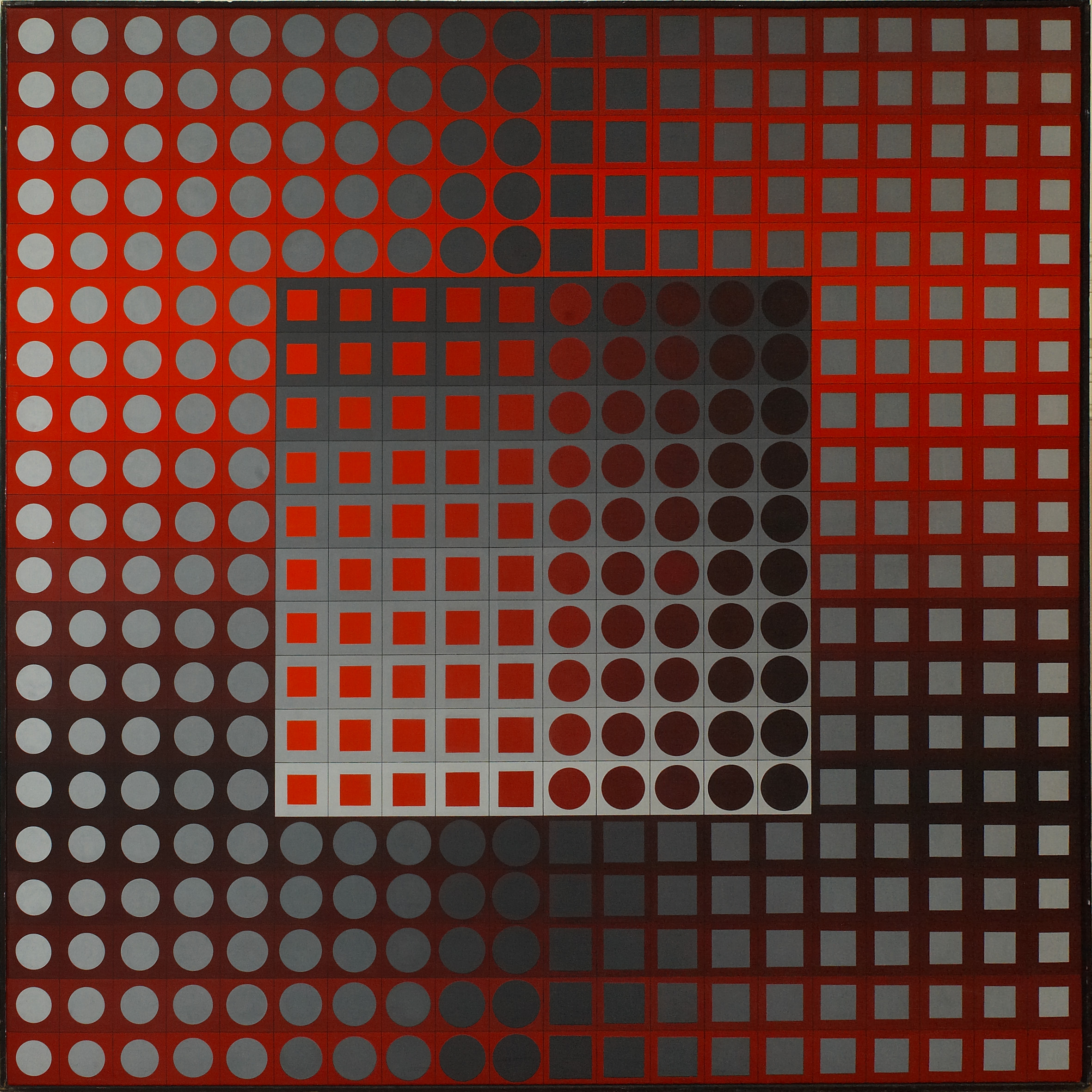

Oil on canvas

160 x 160 cm

Before going further, we should mention Vasarely’s solo exhibitions for the period under study. 1946, 1949 and 1950 in Denmark at the Arne Bruun Rasmussen Gallery in association with Denise René, the exhibition of 1952 there attracting several articles including one by Léon Degand in Art d’aujourd’hui series 3 no. 5, and in 1953 and in the same review by R. Van Gindertaël series 4 no. 2. In 1954 the gallery organised an exhibition at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels as well as an exhibition in Cologne at the Der Spiegel Gallery with Graphiques. 1956 Blanche Gallery in Stockholm and the Artek Gallery in Helsinki, with Jacobsen. In 1958 there was a travelling exhibition that visited Buenos Aires, Montevideo and San Pablo.

In 1959 the Galerie Denise René showed his kinetic works: “Abstraction was only really revealed to me in 1947, when I was suddenly able to recognise that pure form and pure colour signify the world.” Vasarely’s visits at this period to Belle-Île and to Gordes made a decisive contribution to this recognition. His series titled Belle-Île (1947 to 1962) illustrates his rejection of figuration. “Looking at the forms which presented themselves to me and which all came down to ovoids and ellipses, I observed a very striking similarity between things that are apparently opposed.” The pebbles polished by the waves confirmed nature’s inner geometry to him, and in particular the symbol of ‘ocean feeling’ through the ellipse. This was followed in 1948 by the Gordes period. In the Lubéron Valley, where he spent his holidays, he confirmed his earlier fleeting impressions, discovering the architecture of the house made from overlapping cubes. The titles of his works, Kervilahuen, Sauzon and Locmaria, evoke the great rhythms of nature, with wide flat bands of contrasting colour.

Around 1950, the Cristal period shows geometrical forms which, according to Vasarely, can be considered as “purely abstract thanks to the systematic use of axonometric perspective begun earlier and the triumph of pure composition… picture plane or rigorous abstracts, few in number and expressed with a few colours (flat mat or shiny) have on the entire plastic surface: positive-negative”. Very significant are the different versions of l‘Hommage à Malevitch (1952 to 1958). Between 1948 and 1961, with a strong concentration in 1951, he developed the theme Denfert, from the name of the metro station with its finely cracked earthenware tiles which he carefully observed every day (at the time he was living at Arcueil), giving birth in him to obsessional landscapes reminiscent of those around the villages in the Lubéron.

This abstraction derived from Mondrian’s plasticism continued to attract Vasarely’s sensitivity. He also became interested in photographic techniques and made Photographismes, shown in 1952 at the Galerie Denise René: these were small ink drawings enlarged by a photographic process to 4 metres by 3 metres. The superposing of negatives and positives generated complex, unexpected forms. By fixing these on Perspex and separating them, he attained three dimensions. The origins of Œuvres profondes cinétiques are to be found here. The same year he participated in the first group of Charles Estienne’s exhibition La Nouvelle École de Paris at the Galerie de Babylone. His profound difference of opinion with the critic following his refusal of the Kandinsky Prize which he had just been awarded (cf. L’Observateur no. 91, 17 February, no. 92, 24 February 1952— letters mentioned in the catalogue Charles Estienne, CNAC, 1984), a prize which Vasarely considered to be “total fantasy”. In 1954 Vasarely worked on a project for the University City of Caracas, making a panel in aluminium leaf and graphics on Perspex, the composition of which alters as the spectator moves around it.

In November 1955 there followed his exhibition Les éléments de la plastique cinétique at the Galerie Denise René, prefaced by Michel Seuphor, who wrote: “Malevitch’s black square is a window opened through which Vasarely leaps into air. He enters the war of movement, opening all the doors to quarrels, the draft is king… If it is not the object that moves it is the spectator, all is movement, all is space,” he wrote in the Manifeste jaune, which defines the fundamentals of kinetics. Although the principle is already to be found in Alber’s Exercices en transformation sur une surface, Vasarely takes its origins much further back in time: “To give you an approximate idea of the plane which ‘moves’, I refer to the Anges musiciens of the École d’Avignon, where the tiling in front of the angels constantly moves. We see cubes which compose it sometimes above, sometimes below; the vertical sides of the cubes alternatively in light or dark colours change position, decomposing or recomposing with the top or bottom of a cube. This very well-known phenomenon is of course just an interaction of geometrical elements.”

This is how he explains his conception of movement, suggested by the optical illusion based on the principle of what he calls ‘plastic unity’, that is to say the use of a vocabulary of signs and colours: basic geometrical figures undergo gradual deformation and 20 clear colours, of which 6 or 8 vary from very light to very dark, at the same time as a variation on grey. Until 1960 this “plastic unity” consisting of two contrasting forms-colours was based on black and white (Pierre Gueguen: Vasarely, le blanc et le noir, Aujourd’hui, January 1956). It is “composed of two geometrical elements that fit into each other, combine and permutate… From here [he] defined [his] unity by a very simple equation: 1 = 2, 2 = 1, that is to say [that he] took as the basic element a square acting as background and containing a geometrical form, a smaller square, a circle, an ellipse, a rectangle, a triangle, etc.” Kinetics were born and the Galerie Denise René was to be its headquarters.

The tone was set in April 1955 with an important overview that summed up art in movement: older figures such as Calder and Marcel Duchamp were joined by younger artists such as Agam, Bury, Jacobsen, Soto, Tinguely and Vasarely. The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue titled Petit mémento des arts cinétiques by Ponthus Hulten. The gallery became the stronghold of artists whose works suggested movement through a trompe-l’oeil effect, or which proposed real movement by mechanical processes. The aforementioned artists were joined by Schoffer, Kosice and Boto, who all took part in exhibitions focused on movement. It should be recalled that it was the Galerie Denise René which gave the first exhibitions in France in 1957 of the works of Mondrian (who died in 1944) and Albers (who died in 1976).

Vasarely, whose international reputation was growing, had already participated for several years in a large number of group exhibitions. First those held at the Galerie Denise René: 1947 Peintures abstraites. 1948 Sculptures et peintures contemporaines by Léon Degand and Charles Estienne; Tendances de l’art abstrait. 1949 Quelques aspects de la peinture présente. 1950 Quelques aspects de l’art d’aujourd’hui; Espaces nouveaux, presentation by Vasarely with the participation of Le Corneur, Estienne and Aurel. 1951 Formes et couleurs murales. 1952 12 tapisseries inédites woven by Tabard at Aubusson, as well as in 1954, presented in 1955 at the Blanche Gallery in Stockholm and in 1956 at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro; Diagonale. 1953 Œuvres récentes avec Dewasne, Deyrolle, Jacobsen, Mortensen: Denise René présente….

1954 1946–1948 works by Dewasne, Deyrolle, Jacobsen, Mortensen, Vasarely; 2e album de sérigraphie en collaboration avec Art d’aujourd’hui (Atelier Arcay).

1958 Hommage à Léon Degand. In 1949, Denise René organised a number of exhibitions outside France in which the artists of her gallery participated, sometimes alongside foreign artists, making an effective contribution to the distribution of French abstract geometric art: 1949 in Copenhagen and Linien. 1951 Klar Form 20 artistes de l’École de Paris in Copenhagen, Helsinki, Stockholm, Oslo and Aarhus. 1953 Exhibition of Italian and French abstract art in Rome and Milan; at the Hamburg Völkerkundemuseum Magnelli, Arp, Dewasne, Domela, Herbin, Vasarely, Mortensen, Deyrolle, Jacobsen, Bloc.

1954 APIAW (Association pour le Progrès Intellectuel et Artistique de la Wallonie) Liège Bloc, Dewasne, Deyrolle, Herbin, Mortensen, Poliakoff, Vasarely. 1955 Museum of Modern Art, Brazil; Kassel Documenta, participation of the gallery at the International Exhibition Art du XXe siècle with Albers, Arp, Bill, Calder, Ernst, Hartung, Herbin, Lardera, Léger, Magnelli, Mortensen, Taeuber-Arp and Vasarely. 1956 10 ans de peinture française 1945–1955 at the Musée de Grenoble with Sonia Delaunay, Hartung, Lapicque, Léger, Magnelli, Deyrolle, Herbin, Mortensen and Vasarely; International Sezession 1956 Städtisches Museum, Leverkusen, then shown at Baden-Baden in 1957; Art abstrait constructif Galerie Matarasso, Nice. 1958 L’art du XXIe siècle, Palais des Expositions, Charleroi; Dessins et sérigraphies, Mondrian, Mortensen, Seuphor, Taeuber-Arp, Vasarely. 1959 at Leverkusen, Germany. Other exhibitions followed throughout the world at the same time as his solo exhibitions in Paris, Cracow, Zagreb, Budapest, Venice, Dublin and New York.

Vasarely also took part in the Salon des Surindépendants, and very regularly at the Salon de Mai from 1948 onwards, and also at the Réalités Nouvelles. He was invited to participate in l’École de Paris at the Galerie Charpentier in 1954 with Iglo, 1955 Bükk, 1956 Riukiu and 1959 Yarkand III, Longsor II, Kara III.

In 1952 the Galerie Denise René published the first monograph on Vasarely’s work by the artist Jean Dewasne. Vasarely began to compose his theoretical writings in 1955. In his aspiration to a total form of art – integrated in contemporary architecture, which would combine in an immense synthesis painting and sculpture (terms that were in his eyes outmoded), architecture and town planning, in plastic creation that would be bi-, tri- or even multi-dimensional – he demanded a democratic art, accessible to all. Hence the concept of ‘multiples’ rather than reproductions. These runs of a work intended to be multiplied led to the constitution of teams of helpers working on programmes. This pre-supposed a plastic alphabet of 15 root forms cut mechanically in bright coloured paper (20 tonnes) comprising 6 different ranges (red, blue, green, mauve, yellow, grey) going from the lightest to the darkest tone, with a return to colour from 1960. Each element was mobile and interchangeable. Everything was coded in letters and figures, like the silk weave box. Unfortunately this process, amplified by computer, was recovered for commercial ends by certain individuals, removing all intrinsic value from the object, which had been one of the aims sought by the artist. Refuting all romanticism, all expression and all non-lyrical abstraction, Vasarely claimed recognition for the industrial artist. Employed by architects, he attempted the integration of these coloured elements as coverings in different buildings: Hall of the Gare Maine-Montparnasse in Paris, the RTL building in Paris, the Faculté des Lettres in Montpellier, the Jerusalem Museum, The French Pavilion of the 1967 Universal Exhibition in Montreal and the Grenoble skating ring. Today, although he is known worldwide, his legacy and the influence of his creations have not always been well assimilated.

In 1961 he settled at Annet-sur-Marne.

Prix de la Critique in Brussels. Gold Medal at the Milan Triennial. International Valencia Prize in Venezuela. 1964 Guggenheim Prize in New York. 1965 Grand Prize for Print Making in Ljubljana and Grand Prize at the São Paulo Biennial. 1966 Prix de la 1st Cracow Print Biennial.

1963 Rétrospective. Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. Catalogue.

1969 Vasarely Retrospective, Fine Arts Palace, Budapest.

1993 Hommage à Vasarely. Rétrospective 1947–1987, Centre Noroit, Arras. Catalogue.

He was appointed honorary professor of the School of Fine Arts, Budapest.

Vasarely’s son Yvaral (born in 1934) continued his father’s kinetic research, exploring the infinite possibilities of the visual field, which should naturally lead to the fields of architecture, graphics and teaching. He has shown at the Galerie Denise René since 1958.

In 1970 the Vasarely educational museum opened at Gordes (Vaucluse). Catalogue by Claude Desailly, 1971. It is devoted to the preservation and promotion of his work. In 1975 the Fondation Vasarely was inaugurated at Aix-en-Provence.

Vasarely’s work is represented in many museum collections throughout the world. We should mention the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, and the museums of Saint-Etienne – Marseille – Tourcoing – Nantes – Budapest – New York.

- Guy Habasque: Vasarely et la plastique cinétique, Quadrum 3, Brussels, 1964.

- Marcel Joray: Vasarely, a luxury album made by the artist. A large number of plates that explain the development of his work. Ed. du Griffon, Neuchâtel. 1966.

- Werner Spies: Vasarely, P. Tisné, Paris, 1969.

- Entretiens avec Vasarely par Jean-Louis Ferrier. Belfond, 1969.

- Frank Popper: L’art cinétique, Gauthier-Villars, Paris, 1970.

- Gaston Diehl: Vasarely, Flammarion, 1972.

- Werner Spies: Vasarely, Cercle d’Art, 1972.

- Among Vasarely’s many writings: Plasti-Cité. Coll. MO, Casterman Poche, 1970.

Excerpt from L’École de Paris 1945–1965: Dictionnaire des peintres

Ides et Calendes Editions, courtesy of Lydia Harambourg

www.idesetcalendes.com

les artistes

- Karel Appel

- Jean-Michel Atlan

- Martin Barré

- Jean-René Bazaine

- Roger Bissière

- Victor Brauner

- Camille Bryen

- Serge Charchoune

- Corneille

- Olivier Debré

- Jean Dubuffet

- Maurice Estève

- Jean Fautrier

- Otto Freundlich

- Roger-Edgar GILLET

- Hans Hartung

- Jean Hélion

- Auguste Herbin

- Asger Jorn

- Wifredo Lam

- André Lanskoy

- Alberto Magnelli

- Alfred Manessier

- André Masson

- Georges Mathieu

- Serge Poliakoff

- Jean-Paul Riopelle

- Gérard Schneider

- Pierre Soulages

- Nicolas de Staël

- Victor Vasarely

- Bram van Velde

- Geer van Velde

- Maria Elena Vieira da Silva

- Otto Wols

- Zao Wou-ki