Maria Elena Vieira da Silva

1908 - 1992

Maria Elena Vieira da Silva had the rare privilege of very early on being considered as one of the major names of abstract painting without having sought to be recognised as such.

Vieira was born into a bourgeois family. Her grandfather had founded the Seculo, Lisbon’s leading daily newspaper, and her father, a diplomat, died when she was two years old. She was brought up by her mother and aunt, and these two ladies did not prevent her from becoming an artist. Her childhood was punctuated by several journeys: to England (1913), where at Hastings she attended a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which was to remain very present in her recollections; to Switzerland; and to France. She was given piano lessons, and music occupied an important place in her life. In 1917 she attended a performance of the Russian Ballet in Lisbon. At the age of 11 she began to receive drawing lessons from Signora Emilio Santos Braga, and in 1922 studied painting with Armando Lucena, professor at the Beaux-Arts in Lisbon. In 1924 she studied sculpture. In 1927, fascinated by anatomy, she attended classes at the School of Medicine, which came under the studies at the Beaux-Arts.

“ I look at the street, at people walking on foot with different appearances advancing at different speeds. I think of the invisible threads which manipulate them. They are not allowed to stop, I can’t see them anymore, I try and see the machinery which organises them. I think this is in a way what I attempt to paint. ”

In 1928 she moved to Paris, enrolling in Bourdelle’s sculpture classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and exhibiting for the first time at the Salon des Artistes Français. She was deeply impressed by a Bonnard exhibition at Bernheim Jeune, and on a visit to Italy discovered the Sienese School. In 1929, after spending a few months in Despiau’s studio at the Académie Scandinave, she gave up sculpture for good to concentrate on painting, which she studied with Dufresne, Waroquier and Friesz, who taught on the same premises. In the evening she took printmaking classes at Hayter’s studio. She attended Fernand Léger’s Académie and also created fabric designs in a workshop in rue des Petits-Champs in addition to abstract designs for rugs. In 1930 she married the Hungarian painter Arpad Szenes, whom she had met at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. The couple moved into the Villa des Camélias (ref. text by Szenes). Together they visited Hungary and Transylvania. In 1931 they attended a meeting of the ‘Amis du Monde’, a group of Communist sympathisers who defended a social form of art. They became friends with several artists including Hayden, Pignon and Estève. Until 1939 they spent each summer in Portugal.

This is where her inner journey began, which may be compared to a reverie. Through a plastic universe composed of silence and light, she developed a graphic architecture subject to the laws of gravity and to the three dimensions, in which space increased or decreased, and which only emphasised an attraction to emptiness. Several events contributed to establishing a very personal vocabulary that became the artist’s signature. The metallic architecture of the transporter bridge in Marseille (which today no longer exists), seen in 1931, was her ‘revelation’, she often explained. It had permitted her to understand the fragmentation of space.

Oil on canvas

33,7 x 41,7 cm

Tempera on paper

67 x 67 cm

The following year she met Jeanne Bucher, who at that time had a gallery in rue du Cherche-Midi. Through the famous art dealer she met the Uruguayan artist Torres-Garcia, who lived in Paris and ran the ‘Cercle et Carré’ movement and whose works she saw at the Galerie Pierre Loeb. His geometrical painting was based on diagrams and rhythms, combining the symbolic and the formal. Vieira bought several works which she kept for the rest of her life. When Torres-Garcia returned to his country in 1944, a correspondence began between the two artists. He helped her and her husband when they sought refuge in Brazil. All this simultaneously brought back childhood memories, such as the terraces of houses squashed into the narrow lanes of Lisbon, and more recent memories of Sienese paintings with their designs like coloured mosaics.

Another important influence were azulejos – the small squares of multi-coloured ceramics used in Portugal to decorate the interior and exterior of houses – with which Vieira, who possessed an exceptional collection, had decorated part of her studio, thereby increasing its space, which opened onto a coloured infinity. Cities with the scaffolding and tubular framework of buildings under construction, metal station halls, the metro, rails and switches were all sources of inspiration.

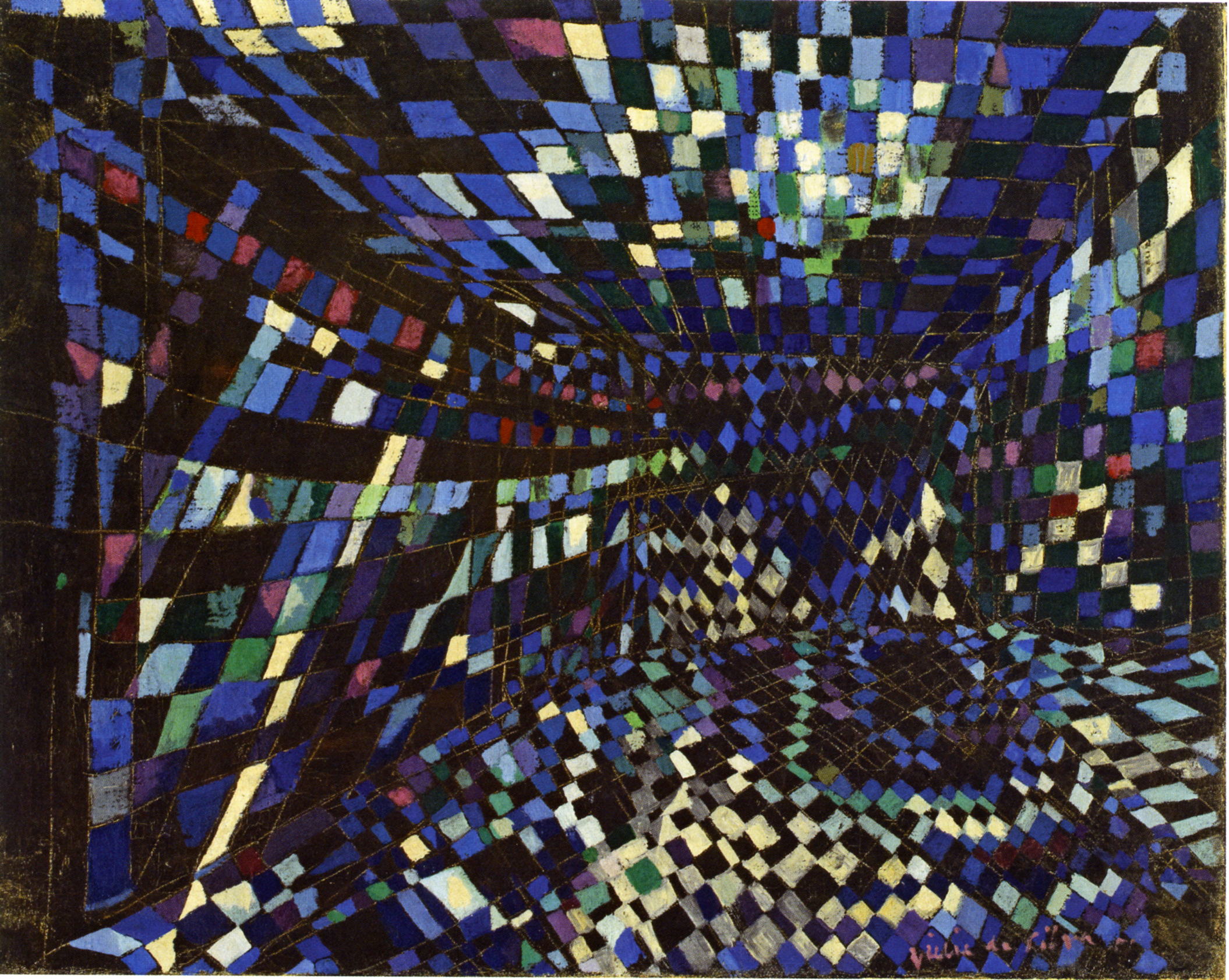

By 1935 Vieira had begun to find her style and subject matter, in particular the labyrinth into which she leads us, simultaneously pulling us and denouncing the traps in the spider’s web of a room with its many closed doors. Typical of this period are works such as L’atelier, Lisbon 1934 (priv. coll.), and above all La chambre à carreaux 1935 (coll. J. Trevelyan, London). The convergent lines of a subtle style support transparent partitions that soon become a chequered system. Resolutely non-figurative, she places herself at the centre of her creative process, as the intermediary between her emotions, her vision of the outside world and the spectator. A work by Vieira operates on several different levels. Exercising a very subtle sensitivity, she produces from her linear world a balance that opens onto a mirror of emptiness and the secrets of our memories matched to the furthermost frontiers of drawing. This is a world of expectancy and immobility, but not of tranquillity.

Her painting is characterised by a certain complexity, with its very specific manner of dividing up space, and superimposing, combining and altering the picture plane through the emotional force of the line, its direction on the surface and the introduction of the time factor in the combination of space and surface. It evokes a world of anxiety, fluctuation, constraints and suffocation. During this period of struggle, doubt and speed, Vieira da Silva’s work conveyed a relevant understanding of the realities of our time, in which the ability to adapt is a prerequisite. Several works may be mentioned that contribute to the development of this theme: Le jeu de cartes 1937 (Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris), La forêt des erreurs 1941 (coll. Marian Willard Johnson, New York) and La partie d’échecs 1943 (Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris).

In 1932 Vieira attended Bissière’s classes at the Académie Ranson. The following year Jeanne Bucher gave Vieira her first solo exhibition. It showed Koko, a children’s book by Pierre Guéguen illustrated with stencil drawings, preparatory notes, a few paintings and a Christmas tree decorated with works that had been cut up by the artist. In 1935 her first exhibition at the Gallery UP in Lisbon took place, and the couple remained in the city until the following year, showing abstract works in their studio. In 1937 the Galerie Jeanne Bucher, which had now moved to the boulevard du Montparnasse, held a second exhibition of Vieira’s work. Marie Cuttoli, who had opened a weaving workshop in Algiers, asked Vieira and Szenes to make copies of works by Braque and Matisse, with whom they had long conversations about colour.

In 1938 the couple moved into an apartment on the boulevard Saint-Jacques. With the outbreak of war, however, they returned to Portugal after having placed their studio and its contents in Jeanne Bucher’s safekeeping. In June 1940 they sailed for Brazil and Rio de Janeiro, where they lived until 1946. Involving themselves in Brazilian intellectual life, their studio became a meeting place for the many young artists who were influenced by their work. Vieira had several exhibitions, and in 1943 made ceramic decorations for the restaurant at the agronomic University. In 1946 her first exhibition in New York took place at the Marian Willard Gallery upon Jeanne Bucher’s instigation.

In March 1947 Vieira and her husband returned to France. In June the Galerie Jeanne Bucher held an exhibition of her work. Pierre Loeb visited her studio and, extremely impressed by what he saw there, held an exhibition in his gallery in June 1949. In the preface to this exhibition Michel Seuphor wrote: “Little by little, developing her familiar subject matter, Vieira da Silva has created an irreplaceable form of art, a rare state of painting. Something is to be found there which has never been expressed before: a space without dimensions, both limited and limitless, a staggering mosaic where each element possesses an inner strength which immediately transcends its own sphere. Each stain of colour possesses a restrained dynamic force that influences the entire painting.” The gallery exhibited her again in 1951 and also in 1955 with a presentation by René de Solier: “In Vieira da Silva’s painting, despite the presence of the world, the elements of the work, the ‘objects’ of her paintings, are considered as if they are seen and ‘felt’ from the interior. There is here a sort of reverse effect, a blind suppression of the world and the creation of a state, an intermediate condition: Night and day.”

Discrete in her French appearances, she nevertheless exhibited at the bookshop-gallery La Hune, showing gouaches with Reichel in 1950. In the same year she exhibited at the Blanche Gallery in Stockholm, at the Galerie Dupont in Lille in 1952, at the Redfern Gallery in London in 1952 and 1953, at the Cadby Birch Gallery in New York, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam with Germaine Richier in 1955, at the Saidenberg Gallery in New York and at the Museum of Modern Art in Basel. In 1956 she showed at the Galerie du Perron in Geneva (with a catalogue text by René Berger) and the Hanover Gallery in London in 1957, with a first retrospective at the La Kestner Gesellschaft in Hanover in 1958, and then presented at the Kunsthalle in Bremen and at Wuppertal (catalogue), followed by the Knoedler Gallery (with a catalogue text by Guy Weelen) in New York in 1961. She made her first visit to New York for the event, and the city was subsequently to serve her as a source of inspiration. In 1963 and 1966 she showed at the Phillips Art Gallery in Washington DC and the Kunsthalle in Mannheim in 1962.

In Paris in 1951 the Galerie Jeanne Bucher showed a series of gouaches for the publication of Et puis voilà, stories told to her doll by Marie-Catherine Bazaine (published by Jeanne Bucher). It was not until 1960 that Vieira exhibited at the gallery again, with a catalogue introduction by René Char. This return was marked by a considerable number of laudatory articles: Frank Elgar in Carrefour on 30 November 1960, Waldemar-George with Les espaces imaginaires de Vieira da Silva in Combat on 17 November 1960, Roger Van Gindertaël in Beaux-Arts Bruxelles on 2 December 1960, Jacques Lassaigne in Pensée française no. 12, New York December 1960, Guy Weelen in Pour l’art no. 71 Lausanne May-June 1960, to mention just a few, and René Barotte, who defended traditional figurative painting in Triomphe d’un grand peintre français in Paris-Presse l’Intransigeant on 26 September 1961.

In 1961 the gallery exhibited 25 engravings illustrating a series of poems by René Char titled L’inclémence lointaine. These engravings were then shown in New York and Washington, and in 1963 at the Gravura Gallery in Lisbon and the Musée Bezalel in Jerusalem. A further exhibition was held at the Galerie Jeanne Bucher in 1967 (catalogue, with a preface by Gaëtan Picon). From 1969 to 1970 Les irrésolutions résolues, large works in charcoal with an introductory poem by Michel Butor. At the same time the Galerie Jacob showed a series of gouaches done between 1945 and 1967. 1971 recent temperas to mark the publication of Dora Vallier’s book La peinture de Vieira da Silva, Chemins d’approche (Weber). This was reprinted by Galilée in 1982, and the gallery showed a series of drawings. 1986 La densité et la transparence, peintures récente, with a preface by Jean-François Jaeger.

Vieira was invited to participate in a number of group exhibitions, among which were: 1952 Nouvelle École de Paris, Galerie de Babylone, Paris, with a text by Charles Estienne. 1953 Vieira da Silva, Ph. Martin, H. Marshall, Kunsthalle Bern (catalogue). 1954 Bissière, Schiess, Ubac, Vieira da Silva et Germaine Richier, Kunsthalle Basel, with a preface by Pierre Guéguen. In 1955 she obtained the Third Prize at the Caracas Biennial. In 1950 and 1954 she showed at the Venice Biennial. 1952 to 1955 and 1958 Pittsburg international Exhibition, Carnegie Foundation. In 1962 she obtained the Grand Prix International de Peinture at the Sao Paulo Biennial. Salon de Mai 1952, 1953, 1954, 1957, 1959, 1961, 1962, 1965, 1967, and Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. 1954 École de Paris, Galerie Charpentier; 1955 Espace nocturne; 1956 La cathédrale; 1957 Port dans le Nord; and 1958 Le grand atelier.

In 1948 the state acquired La partie d’échecs (1948), inaugurating a regular policy of acquisition for Vieira da Silva’s works. La bibliothèque (1949), Jardins suspendus (1955) and L’été ou composition grise (1960) followed. This policy was echoed by regional museums: L’écluse glacée (1953) in Lille, Les tours (1953) in Grenoble, Rouen (1966) in Rouen. Extending her work in other fields, Vieira da Silva worked for several years on tapestry-making, creating life-sized cartoons. She was awarded the First Prize for Tapestry from Basel University in 1954 (tapestries shown at Baie in 1960); these works were executed under the supervision of Marthe Guggenbull, then for the Gobelins, Beauvais and Aubusson tapestry workshops.

Following a proposal by Jacques Lassaigne, she made her first stained-glass window at the Atelier Jacques Simon in Reims in 1963. It was bought by the state. Between 1968 and 1971 she made some more windows, with Charles Marq, for the church of Saint-Jacques in Reims.

Throughout her life Vieira made prints. In 1955 she made a series of screen prints at the René Bertholo and Maria Lourdes workshop. In 1971 she tackled lithography, making a series exhibited that year at the Galerie Jeanne Bucher.

Naturalised as a French citizen in 1956. Since 1956 Vieira had lived and worked in a new house which had been designed for her by the architect G. Johannet on a plot acquired in the 14th arrondissement. In 1954 Guy Weelen, an art critic who had been a friend since they met in 1949, was given the responsibility, at Vieira’s request, for distributing her work, so that she could concentrate entirely on her art. A lengthy process, still in progress, now began of filing archives, cataloguing works, writing a biography (Hazan, 1st edition in 1960, reprinted in 1973) and organising and hanging exhibitions.

A complete biography and bibliography, prepared by Guy Weelen, can be found in the catalogue of the retrospective held in Paris in 1988 – notably for the period after 1965. The work in this exhibition is not described here. It will suffice to say that the apparent simplicity of the subjects covers the complexity of a lasting poetic plastic language. The artist wrote: “I look at the street and at people walking on foot with different appearances advancing at different speeds. I think of the invisible threads which manipulate them. They are not allowed to stop, I can’t see them anymore, I try and see the machinery which organises them. I think this is in a way what I attempt to paint.”

Grand Prix National des Arts in 1963.

Since 1969 to 1970 there have been a succession of retrospectives: Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris. Catalogue, with texts by Guy Weelen, Jean Leymarie and Claude Esteban. Then at Rotterdam, Oslo, Basel and the L. Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon.

1971 Musée Fabre, Montpellier. Catalogue prefaced by Georges Desmouliez.

1977 Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris: Peintures à tempera 1929–1977. Catalogue, with texts by Jacques Lassaigne and Jean-Pierre Faye.

1988 Retrospective in the form of a tribute for the artist’s 80th birthday. Grand Palais Paris. Catalogue. Claude Roy and text by 35 poets and writers.

There have been several prestigious exhibitions of the prints since 1972 at the Musées de Rouen and Cherbourg, and in 1981 at the Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris with the two important donations made by the artist in 1971 and 1981, completed by Jean-François Jaeger’s donation of 1981. Catalogue prepared by Françoise Woimant.

Vieira da Silva’s work is present in many museums with, in France, the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris (Centre Georges Pompidou), for which the artist made numerous donations, as well as to the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. In 1976 an important donation of drawings with works by Arpad Szenes was made to the Musée National d’Art Moderne, where they are shown next to paintings and tapestries belonging to the state (catalogue) – Dijon Donation Granville – Colmar – Reims – Dunkerque – Lyons – Grenoble.

We should also mention Rotterdam – London – Basel – Lausanne – San Francisco – New York – Washington – Cincinnati – Essen – Dusseldorf – Lisbon.

From an early date Vieira da Silva attracted abundant comment in the press as well as studies. The first of these was an article in 1949 by Pierre Descargues in the Presses littéraires de France.

- René de Solier: Vieira da Silva, Le Musée de Poche, G. Fall, 1956.

- Guy Weelen: Vieira da Silva. Les estampes 1929-1976, Catalogue de l’œuvre gravé. Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1977.

- Jacques Lassaigne and Guy Weelen: Vieira da Silva, Monograph, Poligrafa, Barcelona 1978, reprinted by Cercle d’Art, Paris in 1987.

- Anne Philipe: L’éclat de la lumière, Interviews. Gallimard, 1978.

- Michel Butor: Vieira da Silva, peintures, L’Autre Musée, La Différence, Paris, 1983.

- Guy Weelen: Œuvres sur papier, L’Autre Musée, La Différence, Paris, 1983.

Excerpt from L’École de Paris 1945–1965: Dictionnaire des peintres

Ides et Calendes Editions, courtesy of Lydia Harambourg

www.idesetcalendes.com

les artistes

- Karel Appel

- Jean-Michel Atlan

- Martin Barré

- Jean-René Bazaine

- Roger Bissière

- Victor Brauner

- Camille Bryen

- Serge Charchoune

- Corneille

- Olivier Debré

- Jean Dubuffet

- Maurice Estève

- Jean Fautrier

- Otto Freundlich

- Roger-Edgar GILLET

- Hans Hartung

- Jean Hélion

- Auguste Herbin

- Asger Jorn

- Wifredo Lam

- André Lanskoy

- Alberto Magnelli

- Alfred Manessier

- André Masson

- Georges Mathieu

- Serge Poliakoff

- Jean-Paul Riopelle

- Gérard Schneider

- Pierre Soulages

- Nicolas de Staël

- Victor Vasarely

- Bram van Velde

- Geer van Velde

- Maria Elena Vieira da Silva

- Otto Wols

- Zao Wou-ki