Pierre Soulages

1919 - 2022

“We should be grateful to Soulages for having been the first, among artists of great talent, never to recount nor to describe. There is never any ambiguity in his work. He never deformed the image of reality to provide himself with a pretext to paint. He never evoked the need to express ‘doubts’ to justify his taste for spreading colour on a canvas. He never mentioned the mystical and metaphysical experiences that this implied, to explain the concentration necessary for his work. He never hid behind idealistic philosophies. He advanced with a style and quality each year higher, and which sometimes attains the ‘sublime’,” wrote his friend the writer Roger Vailland in 1962 (Procès à Soulages, Clarté no. 43, May).

“ The viewer comprehends the painting with his sensitivity and his own experience of the world which is confronted successively by the painting’s proposals. I consider that my painting has always placed itself beyond the question of figurative and non-figurative. I do not start from either an object or a landscape to then deform them, nor on the other hand do I attempt to provoke their appearance through painting. I hope for more from the rhythm, from this beating of forms in space, this division of space by time. ”

Soulages is an abstract painter who makes no reference to nature. His painting is total: simultaneously universe and language, as he explained: “It is what I do which tells me what I am searching. Painting always precedes reflection.” Extremely accomplished from an early age, he stands out as one of the most eminent artists of the post-war generation. His early recognition placed him on the same level as artists a generation older than himself, such as Hartung, Schneider, Vieira da Silva and Bazaine, and enabled him to share their fame. After the war his painting constantly appeared as one of the most profoundly original, positioning its creator as a pioneer of the lyrical abstraction of the École de Paris. He shared with Mathieu the privilege of being among the first to impose gesturality in contemporary French painting, although no artistic relationship yet existed with the New York school, whose representatives Pollock and de Kooning were unknown in Paris until Michel Tapié’s exhibition Véhémences confrontées, held at the Galerie Nina Dausset in 1951. Nevertheless, the development of their work was to take different forms. While Mathieu became interested in calligraphy, Soulages interiorised his expression and became increasingly abstract.

As a pupil at the lycée in Rodez, Soulages became interested in the carved menhirs at the Musée Fenailles, his birthplace, and also in Roman architecture. On a visit with his class to the church of Sainte-Foy at Conques, he decided he would become an artist. Moved by the grandeur and expressive tension of the church’s arches and the space they generated, the adolescent determined “to devote his existence to painting”. He painted winter landscapes, trees without leaves, and blacks which stand out against bright backgrounds. He was interested by the forms made by branches in space. When he was 18 he made a short visit to Paris, where he saw exhibitions of the works of Cézanne and Picasso, discovering a type of painting about which he had previously been entirely ignorant. In 1941 he was called up in Montpellier, where he was attending the École des Beaux-Arts. During the Occupation, to avoid the compulsory work service, he worked as a labourer in the local vineyards.

Oil on canvas

195 x 130 cm

Oil on canvas

195 x 130 cm

Through the novelist Joseph Delteil, a neighbour, he met Sonia Delaunay, who introduced abstract painting to him. In 1946 he settled at Courbevoie and was able to devote all his time to painting. Here he created his first abstract paintings: “I was not interested in expression generated by the deformation of a model present or imaginary, of its ‘expressive’ interpretation, but by the specific qualities which are born, on the canvas itself, from the relations between forms, colours, background and matters – how all this comes to life, creating space, rhythm and light – without reference to a model,” (Soulages, James Johnson Sweeney, 1972). He made large drawings in charcoal and abstract drawings on paper in black or brown against a white background.

He attempted to show at several salons but was turned down. In 1947 he managed to exhibit at the 14th Salon des Surindépendants, a salon without a jury. His paintings, an “impressive symphony of dark tones” (Maximilien Gauthier in Opéra), contrasted with the colourful paintings in the exhibition, and he was noted by Picabia and Hartung, with whom he became friends. He also got to know Fin, Vilato, Goetz, Christine Boumeester and Domela.

He took a studio in rue Schoelcher in Montparnasse. In 1948 he was invited to show at the 3rd Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, where his entry was noticed by O. Domnick who, having just arrived from Germany, was preparing the first exhibition of abstract art since the defeat of Nazism. A painting in black and white by Soulages was reproduced on the poster to announce the exhibition Grosse Ausstellung Französischer abstrakter Malerei held in the Museums of Stuttgart, Munich, Dusseldorf, Hanover, Frankfurt, Kassel, Wuppertal and Hamburg. The exhibition included works by Bott, Del Marle, Domela, Hartung, Herbin, Kupka, Piaubert, Schneider, Villeri and Soulages, about whose paintings the art critic Marietta Schmidt wrote: “Tragic and hard, they give us the indiscernible, serenely, seriously, religiously. Only a Bach largo is able to give us a similar feeling” (in Die Weltkunst, 15 March 1949, reprod.) In Paris he participated in a group exhibition, Prises de terre, a confrontation between abstract artists and ‘revolutionary surrealist’ artists. At this exhibition he met Atlan. The exhibition was also visited by James Johnson Sweeney, curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the first museum curator to show interest in Soulage’s work.

In 1949 Soulage had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Lydia Conti in rue d’Argenson. In these tiny premises, which measured only 5 metres by 4 metres, Hartung had had his first Paris group exhibition in 1947, followed two months later by Schneider. The three names remained associated for a long time. Charles Estienne wrote: “A style of drawing that is simple, virile, almost harsh, with dark warm harmonies, a natural feeling for texture and the specific possibilities of oil paint, and above all, a tone that is both human and concrete, this is Soulages’ contribution to abstract painting” (Combat, 25 May 1949). Michel Ragon wrote that the artist showed himself to be “the strongest and most confident personality” of the new abstract generation (Paru, July 1949). Soulages commented the origin of his works, the structure of which, imposed by the rhythm of large black marks, offered an archetypal organisation: “In 1947 I began to make wide brush strokes (these lines being from the beginning coloured surfaces) to create a mark delivered in a single abrupt movement. Narrative time, that of the line following the eye, was in this way abolished. The duration of the line now eliminated, time was now immobile in a hieratic mark. In these marks made with rapid direct brush strokes, movement is no longer described, it becomes tension, movement in strength, that is to say dynamism” (Jean Grenier, Entretiens avec dix-sept peintres non figuratifs, Calmann-Lévy, 1963).

Although Soulages’ works are related to the aesthetics of their time, they do not present any antecedents. This opening period characterised by movement and writing was described by the artist: “Time seems to be central to my work as an artist, time and its relation to space” (op. cit.). James Fitzsimmons wrote on this subject: “He is always obsessed by the same forms, but these are transformed. The trees and menhirs have become telegraph posts, beams and scaffolding, television aerials, chimneys, neon advertisements or signals. Not that he paints these things I just mean that, like everyone, he has certain forms ‘built inside him’, in his psyche. He reacts to these forms each time he meets them in his surroundings and they appear on his canvas without him really wanting it. We could call these forms ideal but it would be better to call them primordial, or even better archetypes” (Arts and Architecture, Los Angeles, June 1954).

In 1949 Soulages was for the first time invited to take part in the Salon de Mai, where he continued to show until 1957. That year he also took part in a group exhibition held at the Galerie Colette Allendy, Peintures et sculptures abstraites, with Deyrolle, Gilioli, Hartung, Leppien, Marie Raymond, Schnabel and Schneider. From this period onwards he exhibited regularly in America: Painted 1949 at the Betty Parson Gallery in New York, and Figuration et Abstraction at the Museum of Modern Art São Paulo.

Soulages participated in a large number of group exhibitions that illustrated the importance of the French abstract movement and its influence outside France. These included: in 1950 D’une saison à l’autre at the Galerie Colette Allendy with a text by Charles Estienne; Levende Farver at Charlottenborg, Copenhagen; Junger Westen at the Festival de la Ruhr and Berlin; Selection from the Salon de Mai in Tokyo; Young Painters in the U.S. and France, an exhibition organised by Sidney Janis and Leo Castelli which confronted a French artist with an American artist: Matta with Gorky, Dubuffet with de Kooning, Lanskoy with Pollock, Soulages with Kline (the latter moved over to gestural abstraction in 1950). In 1951 he took part in the opening exhibition, Présences of the Galerie de France, at number 3 faubourg Saint-Honoré; Prima Mostra Pittori d’Oggi in Turin and also in 1953, 1957 and 1961; Selection from the Salon de Mai in Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto; Fransk Konst at the Blanche Gallery in Stockholm; Advancing French Art, Phillips Gallery Washington, then in San Francisco, Chicago, Baltimore… events which all contributed to building his reputation in the USA.

1952 Peintres de la Nouvelle École de Paris organised by Charles Estienne, 1st group, Galerie de Babylone Paris; École de Paris organised by the British Council in London, Liverpool and Edinburgh;

26th Venice Biennial; Rythmes et couleurs, Musée de Lausanne; Berliner Neue Gruppe mit französischen Gästen, Berlin; Malerei in Paris heute, Kunsthaus Zurich. 1953 Premier Bilan de l’art actuel, Essai de dialogue entre artistes et critiques, a discussion in public at the Salle de Géographie, number 184 boulevard Saint-Germain in Paris; 2nd São Paulo Biennial; 2nd International Art Exhibition in Tokyo, Osaka, Ube, Fukuoka, Sasho, Nagoya and Takamatsu; Younger European Painters, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

1954 Individualités d’aujourd’hui, organised by Michel Tapié at the Galerie Rive Droite; Divergences, a selection by R. Van Gindertaël under the title Nouvelle Situation; Aspects of Contemporary French Painting at the Parsons Gallery, London; Tendances actuelles de l’École de Paris, Kunsthalle, Bern and Galerie Denise René, Paris; Younger European Painters in Minneapolis, Portland, San Francisco and Dallas. 1955 Eloge du petit format, organised by Michel Ragon, Galerie La Roue, as well as in 1956; Tendencias recientes de la pintura francesa 1945–1955, Museum of Modern Art, Madrid; 3rd International Art Exhibition, Japan, followed by the 4th in 1957, the 5th in 1959 and the 8th in 1965; Documenta I Kassel; The International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh; The New Decade, Museum of Modern Art, New York followed by Minneapolis, Los Angeles and San Francisco; Le mouvement dans l’art contemporain, Musée de Lausanne.

During this extremely active period, Soulages did not exhibit in Paris, although he showed abroad: in 1951 at the Galerie Birch, Copenhagen. In 1952 at the Stangl Gallery, Munich. In 1954 at the Kootz Gallery, New York. In 1955 at the Art Club of Chicago; the Kootz Gallery, New York; and Gimpel Fils, London. Following his collaboration with Roger Vailland on stage sets for Héloïse et Abélard at the Théâtre des Mathurins in 1949, he carried out three commissions for the theatre: in 1951 The Power and the Glory based on a novel by Graham Greene for Louis Jouvet at the Athénée (the play was however not in the end performed because of the actor-director’s death); and a stage set for a ballet by Janine Charrat, Abraham, at the Capitole de Toulouse; and in 1952, as part of the celebrations at Amboise for the 500th anniversary of the birth of Leonardo da Vinci, a mobile decor suspended from large gas balloons (another decor was commissioned from Fernand Léger with whom he got on well). In 1951 he made his first etchings and aquatints at the Lacourière printmaking workshop. These prints were shown in an exhibition at the Galerie Berggruen in 1957 (catalogue text by Roger Van Gindertaël).

Soulages’ painting then went through a transformation. “Around 1955, the mark tends to disappear and brush strokes are juxtaposed, multiplying; through repetition, the relationships that are then established between these almost identical forms create a rhythm, a spatial rhythm. The stronger the rhythm the less the image, I mean the attempt at figurative association, is possible” (op. cit. in Jean Grenier). This rhythm is a constant feature of his work, about which the artist says: “The rhythm that I am talking about originates when I combine one form with another thereby creating the experience of space and its division… the viewer comprehends the painting with his sensitivity and his own experience of the world which is confronted alternately by the painting’s proposals. I consider that my painting has always placed itself beyond the question of figurative and non-figurative. I do not start from either an object or a landscape to then deform them, nor on the other hand do I attempt to provoke their appearance through painting. I hope for more from the rhythm, from this beating of forms in space, this division of space by time. Space and time… have become the instruments of the painting’s poetry” (op. cit.).

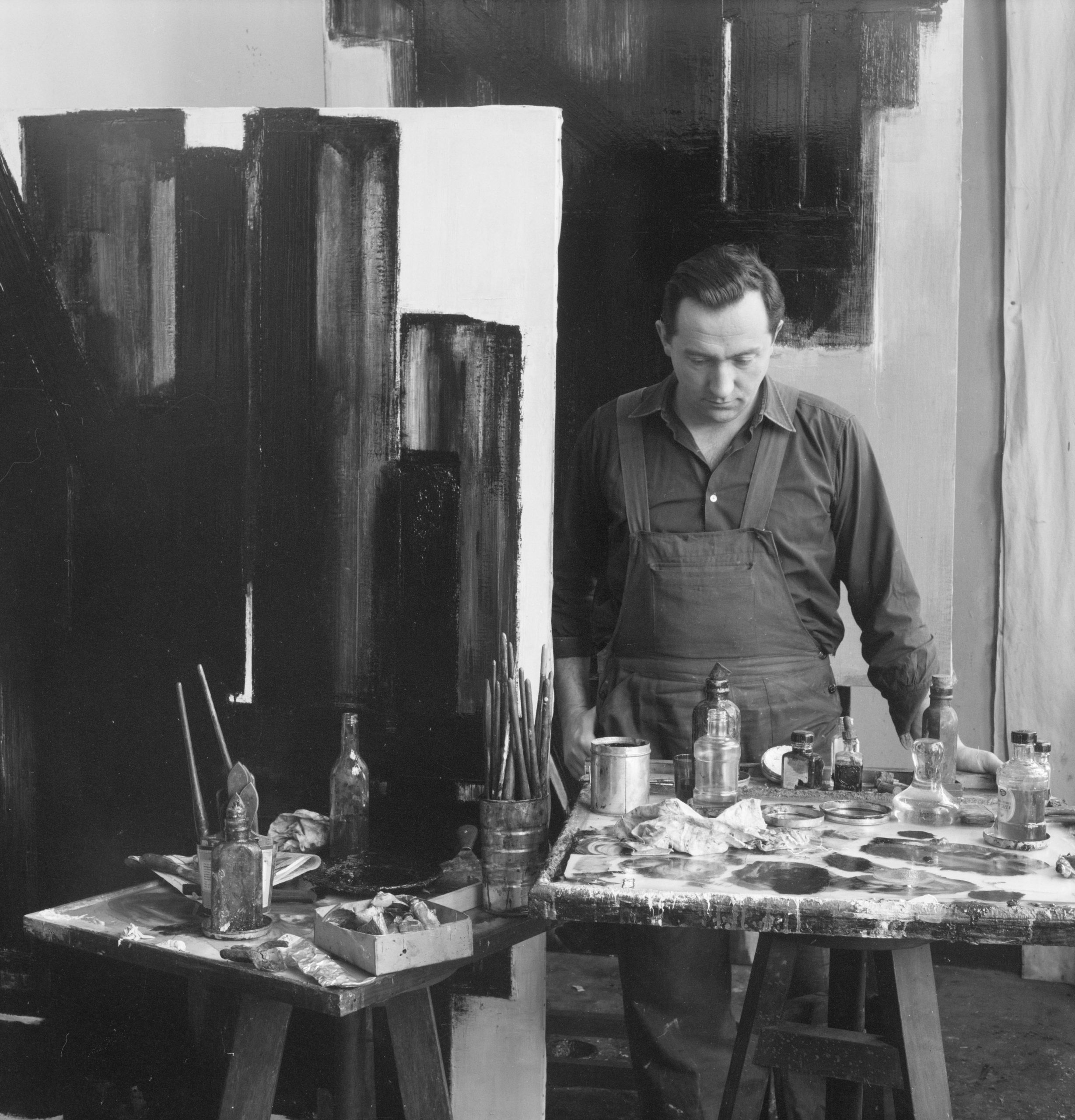

His works acquired a physical weight and density related to the importance he gave to texture: “I like textures that change, time trapped by textures.” He worked with instruments that were unusual for a painter: tools used by book binders, tanners, carpenters or bee-keepers. His passion for techniques and tools encouraged him to make his own tools: wood scrapers, plane blades, palette knives, wide brushes, tiny Chinese brushes, etc. He made himself long-handled brushes to be able to paint standing with his canvas laid on the floor.

1956 first exhibition of a long series at the Galerie de France, 1960, 1963, 1967, 1972, 1974, 1977, 1986 and 1992 (catalogues). In 1957 he moved into a new studio near the church of Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre. He began a new series of etchings. That autumn, he visited the USA, where he met William de Kooning, Rothko and Motherwell. He won the Grand Prix at the Tokyo Biennial. Exhibitions at the Kootz Gallery in New York in 1956, 1957, 1959, 1961, 1964 and 1965 (complete list of solo exhibitions in Soulages, Ides et Calendes, 1991).

In 1958 he travelled to Japan, visiting temples and stone gardens, and interesting himself in calligraphy. In 1959 he built himself a studio above the town of Sète, where he now worked for some of the year. He continued to participate in numerous group exhibitions including: 1956 Festival de l’Art d’avant-garde, Cité Radieuse-Le Corbusier in Marseille; Art français contemporain, Fine Arts Institute Mexico; École de Paris, Munich.

1957 Depuis Bonnard, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris; Nouvelle École de Paris Bridgestone Gallery, Tokyo; Phases, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; 2nd International Print Biennial and the 3rd Biennial in 1959, at which he won the First Prize. 1958 Gravures: Hartung, Schneider, Soulages, Singier, Galerie Aujourd’hui, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels; L’art du XXe siècle, Palais des Expositions, Charleroi; Contemporary Painters, Kunsthalle, Mannheim.

1959 Donation Gildas Fardel, Musée de Nantes; Peintres d’aujourd’hui, Musée de Grenoble; French Painting, from Gauguin to our time, Warsaw Museum; Documenta II Kassel; Twenty Contemporary Painters from the Dotremont Collection, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; L’École de Paris dans les collections belges, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris. 1960 1st Art International Art Exhibition, Museum of Modern Art, Buenos Aires; Antagonismes, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris; French Painting Today, Tel-Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa. 1961 Paris, Crossroads of Painting, Museum of Eindhoven; French Art, Moscow. 1962 École de Paris, Tate Gallery, London; 100 years of painting in France from 1850 to our time, Mexico; École de Paris, Warsaw and Cracow Museums.

1963 7th São Paulo Biennial; Peinture française contemporaine, Musée de Montréal; Französische Malerei der Gegenwart, Haus der Kunst, Munich; Contemporary French Art, Cape Town, Johannesburg, Salisbury; Collection Sonja Henie-Niels Onstad, Musée de Genève; 1st Salon des Galeries-Pilotes, Lausanne. 1964 Painting and Sculpture of a Decade 54–64, Tate Gallery, London; Documenta III Kassel; 1950 The Fabulous Decade, The Free Library, Philadelphia; Painters of Paris, Fondation Mendoza, Caracas. 1965 French Contemporary Painting, Buenos Aires, Santiago (Chile), Rio de Janeiro, Lima, Montevideo; Maîtres de la peinture contemporaine, Musée de Montpellier; A century of French painting 1850–1950, Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon (complete list op. cit.). Invited to participate in l’École de Paris, Galerie Charpentier, from 1955 to 1958 and in 1961.

In the 1960s Soulages broke with the large segments of black bars. In about 1963 a black stain invaded the canvas, abolishing the dramatic contrast of light and shade that had previously existed. Although he made subtle use of colour —luminous blues and reds – his palette remained limited: “The more limited the means, the stronger the expression.” Soulages remains an artist who has given black its full value, and he adds that it “remained the basis of my palette. It is the absence of the most intense and violent colour which gives an intense and violent presence to colours, even to white” (Pierre Schneider Au Louvre avec Pierre Soulages, Preuves no. 143, January 1963). He worked using a subtle range of monochrome tones. “Oil paint, is a dialogue between opacities and transparencies,” he added. This enabled him to lighten certain dark sections of the canvas with blue, green or brown monochrome, at the end of the 1960s and even in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1976 he made a limited series of small paintings with horizontal bands. From 1979 onwards forms – like furrows – and light are defined by brush strokes. The painting’s movement and rhythm become a part of the ‘image’.

1964 Carnegie Prize, Pittsburgh.

First retrospectives in 1960 in Hanover, 1961 Essen, The Haig, Zurich (catalogues).

1967 Rétrospective, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris. Catalogue Bernard Dorival.

1976 Rétrospective, Musée d’Art et d’Industrie, Saint-Etienne. Catalogue Bernard Ceysson.

1979–1980 Pierre Soulages Peintures récentes, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Catalogue.

1984 Retrospective. Seibu Museum, Tokyo. Catalogue, texts by T.O. Okada and Alfred Pacquement.

1989 Soulages, 40 years of painting, Kassel Museum, Julio Gonzalez Centre, Valencia, Musée de Nantes. Catalogue, texts by Veit Loers and Henry-Claude Cousseau.

Soulages is particularly well represented in museums throughout the world, notably in Germany – the USA – Brazil – Japan – Scandinavia – London – Vienna – Jerusalem – Rotterdam – Zurich – Canada and, for France: Paris Musée National d’Art Moderne and Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris – Brou – Caen – Dunkerque – Evreux – Grenoble – Marseille – Metz – Montpellier – Nantes – Rouen – Saint-Etienne – Saint-Paul-de-Vence Fondation Maeght – Toulouse – Valence – Villeneuve-d’Ascq.

May 2014 : opening of the Musée Soulages in Rodez, France.

- Hubert Juin: Soulages, Le Musée de Poche, G. Fall, 1958.

- Michel Ragon: Pierre Soulages (peintures sur papier), F. Hazan, 1962.

- James Johnson Sweeney: Soulages, Ides and Calendes, Neuchâtel, 1972.

- Michel Ragon: Les Ateliers de Soulages, Albin Michel, 1990.

- Pierre Daix-James Johnson Sweeney: Soulages, l’œuvre, Ides et Calendes, 1991.

- Pierre Encrevé, Soulages, l’œuvre complet, Peintures, Vol. I. 1946 – 1959, Seuil, Paris novembre 1994.

- Pierre Encrevé, Soulages, l’œuvre complet, Peintures, Vol. II. 1959 – 1978, Seuil, Paris novembre 1995.

- Pierre Encrevé, Soulages, l’œuvre complet, Peintures, Vol. III. 1979 – 1997, Seuil, Paris octobre 1998.

- Pierre Encrevé, Soulages, l’œuvre complet, Peintures, Vol. IV. 1997 – 2013, Seuil, Paris octobre 2015.

Excerpt from L’École de Paris 1945–1965: Dictionnaire des peintres

Ides et Calendes Editions, courtesy of Lydia Harambourg

www.idesetcalendes.com

Publication

Dialogues

Autour de Pierre Soulages

les artistes

- Karel Appel

- Jean-Michel Atlan

- Martin Barré

- Jean-René Bazaine

- Roger Bissière

- Victor Brauner

- Camille Bryen

- Serge Charchoune

- Corneille

- Olivier Debré

- Jean Dubuffet

- Maurice Estève

- Jean Fautrier

- Otto Freundlich

- Roger-Edgar GILLET

- Hans Hartung

- Jean Hélion

- Auguste Herbin

- Asger Jorn

- Wifredo Lam

- André Lanskoy

- Alberto Magnelli

- Alfred Manessier

- André Masson

- Georges Mathieu

- Serge Poliakoff

- Jean-Paul Riopelle

- Gérard Schneider

- Pierre Soulages

- Nicolas de Staël

- Victor Vasarely

- Bram van Velde

- Geer van Velde

- Maria Elena Vieira da Silva

- Otto Wols

- Zao Wou-ki