THE 50'S IN PARIS

1945/1965

by Lydia Harambourg

The term ‘Nouvelle École de Paris’ was first used in 1952 by the critic Charles Estienne for an exhibition he organised at the Galerie de Babylone in Paris, to avoid confusion between the first École de Paris (constituted from the many artists who had emigrated to Paris early in the 20th century) and the new generation rooted in post-war abstraction. Charles Estienne included under this term most of the artists who symbolised the 1950s, and who had nothing in common with the previous generation.

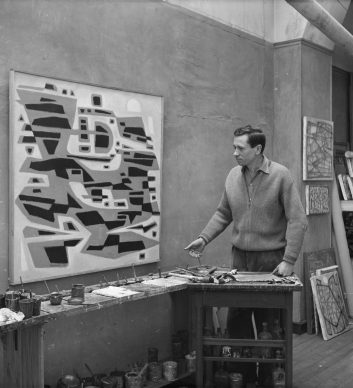

The story began in 1941 with the exhibition Vingt jeunes peintres de tradition française which, under the Occupation, opposed the permanence of art, and which had not yet been liberated from nature and the figure before turning to non-figurative expression. Among these young artists were Bazaine (the initiator), Bissière and Manessier. They constituted the core of what came to be called ‘La Nouvelle École de Paris’. The term ‘school’ is, however, inappropriate, as no form of teaching was dispensed, and the movement was comprised of various currents with a variety of styles derived from the legacies of fauvism, cubism and surrealism (Masson, Lam). Often in conflict with each other, these groups came together and disbanded in response to the aesthetic issues and critical controversies aired in a committed press, where daily newspapers and reviews positioned themselves alongside the dealers and their stables of artists, to promote a new, free form of abstract art, between ‘lyricism and abstraction’ (Restany).

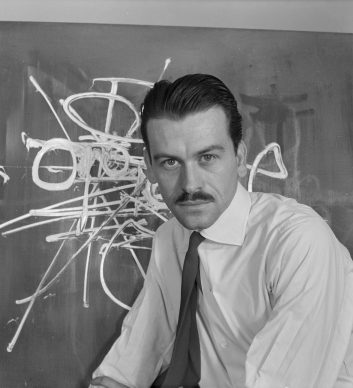

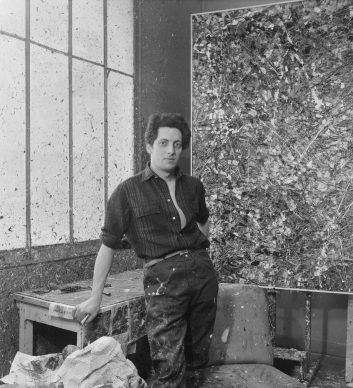

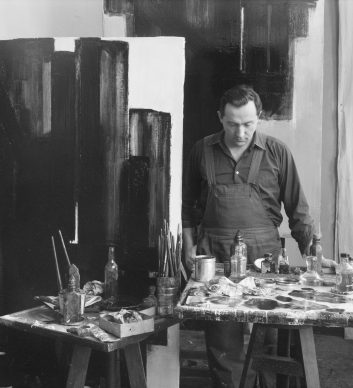

For nearly two decades, the aesthetic of the gesture, speed and its control, and the sign united artists from all over the world in passionate confrontation lived with the freedom, taste for risk and jubilation that characterised these years of struggle.

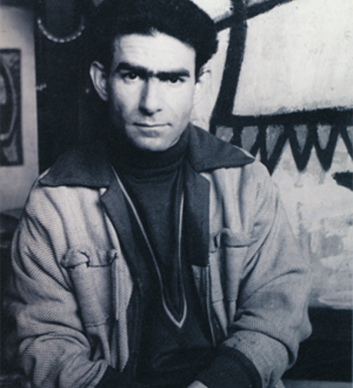

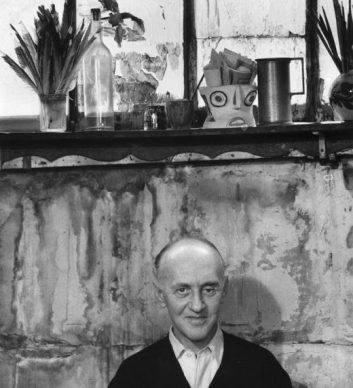

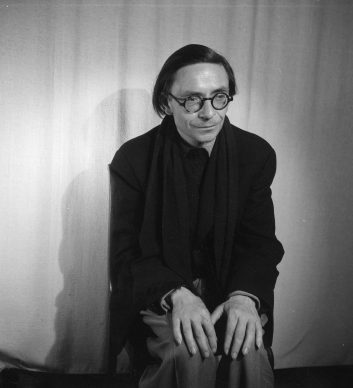

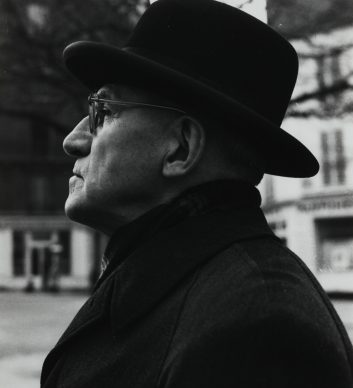

Each of the abstract artists developed their own personal research. Vieira da Silva, de Staël, Fautrier, Hélion, Charchoune, Estève, Atlan (who created a link with Cobra – Jorn, Corneille and Appel), Dubuffet, Bram and Geer van Velde. They were not, however, all lyrical. Denise René defended geometrical abstraction, which included Magnelli, Herbin and Vasarely, while the trio Hartung, Schneider and Soulages counter-attacked at Lydia Conti’s gallery. The Nouvelle École de Paris soon occupied a commanding position. Lyrical abstraction was a success. It proclaimed the gesture, the sign and speed. In 1947 Georges Mathieu brought ‘lyrical’ or ‘psychic’ non-figuration to the public’s attention with a group exhibition that included Wols, Bryen, Atlan and Riopelle, and the following year showed for the first time the American ‘Action Painters’ – Pollock, Tobey and de Kooning.

Lyrical Abstraction was at the centre of the combative debates between critics such as Charles Estienne, Léon Degand, Julien Alvard, Michel Tapié, R.V. Gindertaël, Michel Ragon, Jean-Clarence Lambert and Pierre Restany, before the latter broke with the Nouvelle École de Paris artists.

Space and time became poetic elements. In the work of Olivier Debré, Zao Wou-Ki and Chu the-Chun, nature was considered from a new perspective, which suggested to Ragon the term ‘lyrical landscapism’. Signe paysage and Signe personnage for Debré’s ‘abstraction fervente’; the immanence of the gesture for a lightning style with Hartung, Schneider and Mathieu; lyrical abstraction equally encompassed other designations: art informel, art autre (Tapié) and tachisme.

Texture, rhythm and the symbolism of the sign summoned forms and colours driven by the pressure of a gestural language. The stain met with varying fortunes with Lanskoy, Estève and Manessier. From Saint-Germain-des-Prés to the Rive Droite, galleries blossomed, forming strongholds where the artistic advances testified to intense activity (Pierre Loeb, René Drouin, Paul Facchetti, Jeanne Bucher, Nina Dausset, Pierre Craven, Galerie de Beaune, Galerie de Babylone, Galerie Kléber, Galerie Arnaud…). A single maxim prevailed: not to show figurative work. The artists cohabited on the walls of these galleries and the new salons: Réalités Nouvelles, Mai and Octobre.

For nearly two decades, the aesthetic of the gesture, speed and its control, and the sign united artists from all over the world in passionate confrontation lived with the freedom, taste for risk and jubilation that characterised these years of struggle.

Published in 1993 by Editions Ides et Calendes, Lydia Harambourg’s work L’École de Paris, 1945–1965: Dictionnaire des peintres remained out of print for several years. A new revised edition, published in 2010, provides a response to the growing interest of art-world professionals and members of the general public and reflects the recognition of public institutions. The many symbolic currents of the ‘Seconde École de Paris’, also referred to by critics (who did not always agree with each other) as the Nouvelle École de Paris, has today become part of history. The art historian Lydia Harambourg for the first time discusses the stylistic diversity of this exceptionally creative movement, which ranged from lyrical abstraction to geometrical abstraction, from art informel to figuration and from non-figuration to expressionism.

Lydia Harambourg is a historian, writer, journalist and art critic. A corresponding member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts de l’Institut de France, she is a specialist in 19th- and 20th-century painting and sculpture. She writes a weekly column on exhibitions in the Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot and has curated exhibitions. She has written several works including L’École de Paris, 1945–1965, Dictionnaire des peintres, published in 1993 by Editions Ides et Calendes and recently reprinted. She has also written a number of successful monographs on Bernard Buffet, Olivier Debré, Georges Mathieu and Chu Teh-Chun. She has received a number of awards, including several from the Académie des Beaux-Arts.